AI data centre power and glory - an update

My piece on AI and energy, entitled "The Power and the Glory", got a lot of great feedback. It also predated DeepSeek's big reveal. So here are a few supplementary thoughts, two months later.

On 24 December last year, Bloomberg published a 7,000-word essay on AI that I had spent nearly six months writing, entitled Generative AI - the Power and the Glory. In it, I declared that 2024 was “the year the energy sector woke up to AI... and the year AI woke up to energy”. Within a month, with the launch of the Chinese DeepSeek-V3 model on 20 January this year, it became out-of-date. Or did it?

Generative AI, the Power and the Glory

In my essay at the end of last year, I started at the beginning, with the history of AI and the repeated predictions over the past few decades that data centres would soon consume a vast proportion world’s power. I pulled apart the assumptions behind the frenzy around AI data centres, and speculated on how they will and won’t be powered. Along the way, I looked at how the energy sector itself was adopting AI and what that might mean for demand, and the possible impacts of AI on the broader economy, which could be positive or negative.

If you have not yet read the piece, you might want to do so before reading on. Alternatively, why not listen to it? As with each of my Bloomberg essays, I turned it into an episode of Cleaning Up, though this time I decided not to read it myself: I created an AI avatar I call Mike Headroom (in honour of the 1980s virtual talk-show host Max Headroom, a breathtakingly accurate snapshot of the digital future, dating back to the pre-digital 1980s). Every word you hear in the episode is generated by AI, using my voice.

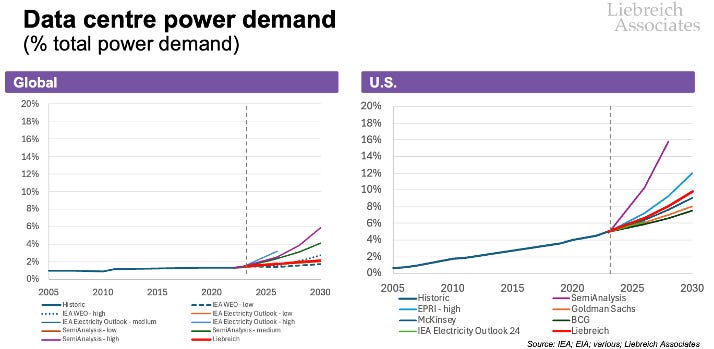

In the Power and the Glory piece/podcast, after reviewing the full range of forecasts by other commentators and analysts, one of the things I did was to come up with my own best estimate for data centre power demand by 2030.

On a global basis, my forecast lies somewhat above the most conservative expectations, but well below the expert consensus as represented by BCG, McKinsey and EPRI - at around an additional 45GW of dispatchable power demand by 2030. If I’m right, demand from data centres would increase from the current 1.5% of global electricity demand to 2.2% by 2030. Significant (particularly in the light of power demand growth over the period), but not overwhelming.

For the US, however, my forecast was much more dramatic. Because of the EU’s high energy costs and climate-related regulatory burdens, and the US export controls on frontier GPUs designed to prevent China from being competitive, I expected the majority of the additional power demand to be in the US. Shoehorn 2/3 of that 45GW of additional demand into a market that only accounts for 1/7th of global electricity, and you end up with US data centre power demand soaring from 5% of total demand today to over 9% by 2030.

Before we rush to invest all our savings and pensions in yet another AI data centre however, let’s put these US figures in perspective.

My dramatic forecast for US data centre power demand pushes total US demand growth noticeably above the EIA’s 2024 outlook, bringing the figure for 2036 forward to 2030. However, this still only results in a total demand growth rate of 1.8% per year - the sort of growth that the US grid used to deliver with ease until 2005.

There are two real issues. The first is that the US, like the rest of the developed world, has had 20 years of unusually low demand growth, which has caused supply chains to atrophy, and now they need to be reactivated. The second is that the additional demand from data centres, particularly training data centres, is extremely concentrated and demanding: gigawatts of demand on one campus, with no tolerance for downtime. That’s a tough call.

From Deep Thought to DeepSeek

So, would I change my predictions if I wrote the piece today, in the light of the sudden arrival on the scene of DeepSeek? The short answer is is no.

At least, not at the global level, though I might revisit the assumption of 2/3 of AI compute being in the US, lowering it to the 40-50% range. That would still mean that of the 45GW of additional dispatchable power globally by 2030, only around 20GW would be in the US, rather than 30GW.

The reason I don’t feel the need to update my global figure is that I anticipated exactly the sort of efficiency breakthrough represented by DeepSeek. I may not have realised how soon it would happen, but here’s what I wrote:

“We could well see power demand limited by stunning improvements in energy efficiency.

“Speed and efficiency improvements can be found within each of these components [of a GPU], but also in the way they work together, as well as in the way the algorithms work.”

“The sector is moving so fast that there are almost certainly innovations out there that could make AI compute dramatically more energy efficient.”

I’m not the only one who feels that we should have anticipated the DeepSeek-V3 achievement.

Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic and creator of the Claude family of AI models, suggests we should not be taken in by claims (heavily promoted by Chinese state-linked accounts) that DeepSeek-V3 only cost $6m to train, noting in a blog post a week after its launch, that the number of GPUs to which the DeepSeek had access would have cost $1 billion.

Amodei also noted that “DeepSeek-V3 is not a unique breakthrough or something that fundamentally changes the economics of LLM’s; it’s an expected point on an ongoing cost reduction curve… We’d expect a model 3-4x cheaper than 3.5 Sonnet/GPT-4o around now”. What surprised him - and me too - was the nationality of the breakthrough team. As he put it,

“what’s different this time is that the company that was first to demonstrate the expected cost reductions was Chinese”

In my piece, I wrote that “China is judged to be five years behind the US”, which may well be true for their ability to match the performance of NVIDIA’s GPUs, but is clearly not true for their AI scientists and software developers.

The other developments of note since the publication of my Power and Glory piece have been in Europe. France held an AI Action Summit in early February, at which President Macron unveiled a €109 billion AI investment plan, and shortly afterwards President Ursula von der Leyen announced the “EU InvestAI” initiative which aims to mobilise €200 billion in AI investment.

Under pressure from Germany, France and business leaders, EU has presented an “omnibus” proposal to simplify rules and remove red tape. As part of this, the Executive Vice-President for Tech Sovereignty, Security and Democracy Henna Virkkunen promised to simplify the bloc’s rules on AI, and the measures also promise to reduce the demands for climate disclosures, which I described in 2021 as “an incredibly intrusive way to drive additional disclosure of marginal utility” and “a considerable overreach”.

Goldman Sachs Research has identified a European data centre pipeline amounting to about 170 GW - sufficient to absorb a third of European electricity - which clearly will not all be built - not by a long way.

Nevertheless, perhaps I was overly pessimistic about both Europe and China’s ability to compete - although uncertainty still abounds as to whether they can procure enough GPUs. That question may be decided based on whether it would help or harm the interests of Elon Musk, who appears to be running (or destroying) large parts of US Government.

It’s about the balance sheet, stupid!

Immediately after publishing The Power and the Glory, I had a few sleepless nights. Was I being overly conservative? But then I did a back of envelope calculation which reassured me that if anything, my 45 GW forecast, which would involve investment of $900 billion between now and 2030, will be on the high side.

Microsoft alone is planning to spend $80 billion on data centres this year - plans it has insisted remain intact despite DeepSeek, and which, if repeated annually through 2030, would amount to $480 billion dollars. BCG reckons that leading data centre players are collectively readying a massive $1.8 trillion deployment of capital from 2024 to 2030. And Steven Schwarzman, CEO Blackstone, the world’s largest alternative asset management company, has said he expects $2 trillion to be spent over the next five years.

Microsoft has a market capitalisation today of $3 trillion. So what is to stop it spending $480 billion dollars, that’s only 15% of its market cap, surely no investor would begrudge it the funds?

Not so fast. Microsoft’s total balance sheet value at the end of December 2024 was only $534 billion. Microsoft does not use its market capitalisation to enter into lease agreements, it uses its balance sheet. Suddenly $480 billion looks like an impossibly large figure. Look at it another way. Wall Street lets Microsoft hang on $534 billion of its cash in equity and debt because by doing so that money is worth $3 trillion. It is worth $3 trillion because Microsoft uses it to provide proven services like Azure, Office, Windows, Gaming and LinkedIn. Of these, only Azure cloud services are particularly capital-intensive, and Azure has a lot of clients that are locked in for multiple years - either contractually or through switching costs.

Now Microsoft is asking for another $480 billion, which it wants to invest in data centre real estate plus GPUs and other equipment - which could have a useful lifetime as short as two or three years.1

It is of course possible that this new $480 billion investment will create new revenue that is as profitable and sticky as its current business. But it is also possible that it does not. And it’s not just Microsoft - all the hyperscalers are making the same bet.

While the combined market capitalisation of the five Western hyperscalers - Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft and Meta - is nearly $13 trillion, their combined balance sheet is only $2.2 trillion. Can you let an industry with a balance sheet of $2.2 trillion invest another $2 trillion in the next five years on the promise that it can create sufficient new cash flows? I don’t think so. [figures updated May 2025]

Of course there are lots of ways of keeping things off balance sheets. Data centres can be built by infrastructure funds and other third parties; GPUs can be bought and leased out by specialist investors (like shipping containers, or aircraft). No doubt billions of dollars of investment banking fees will be earned by creating all sorts of funky structures and new derivatives.

In the end, however, there are only so many places you can hide a trillion or two dollars worth of risk, as the world periodically discovers. Ultimately every investor will need some form of guarantee underwritten by someone with a balance sheet - either a hyperscaler, a corporate who is the ultimate AI customer, a government or some sort of a sovereign entity.

When I wrote the Power and the Glory, I could see two possible futures: “one in which capital markets are happy to allow the hyperscalers to keep throwing money at AI in the expectation of future market leadership (and blowing out their balance sheets in the process), and one in which they are not.” I now think the latter option is far more likely - and by the way, a better outcome for the world.

If they have any sense, investors will wake up from their Midsummer Night’s AI Dream within the next year or two, and reject excessively ambitious data centre plans. If they don’t, I strongly suspect they will live to regret it.

Selah.

Please share this piece…

I hope you found this piece of interest. If you have not yet read Generative AI, the Power and the Glory (or listened to it read by Mike Headroom), it’s not too late to do so. It seems to be standing the test of time reasonably well.

If you are enjoying listening to/watching Cleaning Up, please recommend it to your friends, family and colleagues. Our audience is growing, and you can help. Plus, don’t forget to subscribe to Cleaning Up’s own newsletter: CleaningUpPod.Substack.com.

I was alerted to the issue of short GPU lifetimes after writing my Power and Glory Piece. There is still very little real data. In October 2024 a rumour spread on social media, allegedly based on a conversation with a “GenAI Principal Architect at Alphabet” that with 60-70% utilisation rate, data centres can fail after just three years.

Intrigued, I dusted off my old stats textbooks and did some calculations myself, using data released by Meta from a 54-day training run of Llama 3, using 16,384 NVIDIA H100 GPUs, during which 148 of them failed.

If you assume a constant failure rate (Weibull k factor = 1), it would take 11.3 years for half of the GPUs to fail. However, if you assume that failure rate rises over time due to mechanical wear and thermal stress, things look much worse.

Server hardware is often modelled using a Weibull k factor of 1.5 to 2.0 (according to ChatGPT), which would give a time to 50% GPU failure of 1.3 to 2.7 years.

Yikes!

OK, I confess, I actually got ChatGPT to do the calculations :-)

Given that very few predicted in 2019, that AI would be here in 2025, do not expect consensus will be right on where AI will be by middle of next decade, including energy requirements.

Fast changing world.

Microsoft's total capital may be over $500 billion, but it's net equity is only half of that amount.

Entering into capital leases does not go against the entire balance sheet, only against the equity. In essence, a capital lease is a form of debt. The investors in that debt are not interested in "how much you are worth" without first subtracting your debt. And, in the case of Microsoft, those liabilities (of various kinds) include $243 billion that DOES show up on its balance sheet PLUS the present value of any operating leases (for buildings, equipment, and perhaps Nvidia chips).

The operating leases are not disclosed on the balance sheet; one needs to read all the footnotes in the 10-K to figure those out.

All of which supports Michael's conclusion, that these companies are not going to invest TRILLIONS in new AI data centers. They will invest hundreds of billions of dollars, and that WILL result in increased electricity consumption. In some balancing areas, that will be very challenging -- Virginia at the top of the news.

BUT, even an increase from 4% to 9% of US power consumption is only the amount of load growth that the industry kept up with EVERY YEAR in the 1960's and early 70's.

Perhaps Michael's most important point, in that historical context, is that the supply chains to support electric utility growth are not in place. The generation supply chain is fine -- the world will install 10X the renewable generation required by new AI loads each year. We need those renewables to back out fossil, but generation is not the challenge. Transmission and distribution supply chains, however, are a mess and do need to grow back to previous capacities.